Burmese exile

Mae Sot

Chiang Mai, Thailand

Get Directions →

Burmese exile

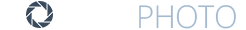

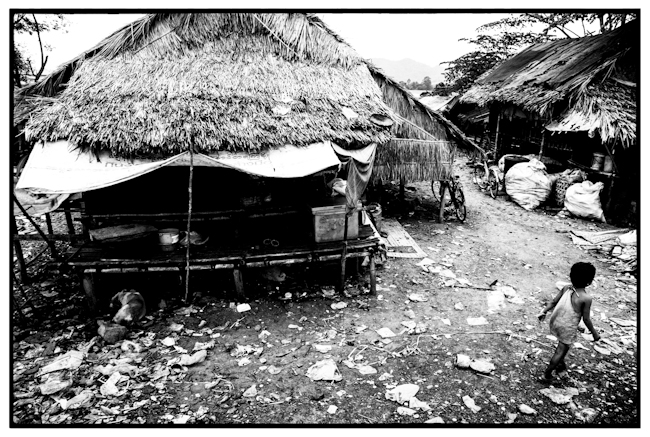

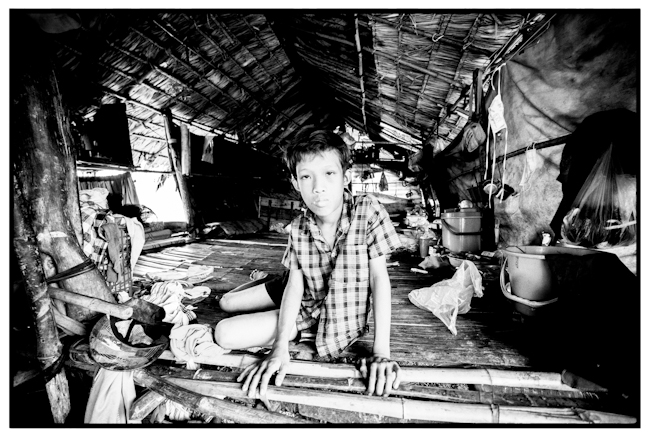

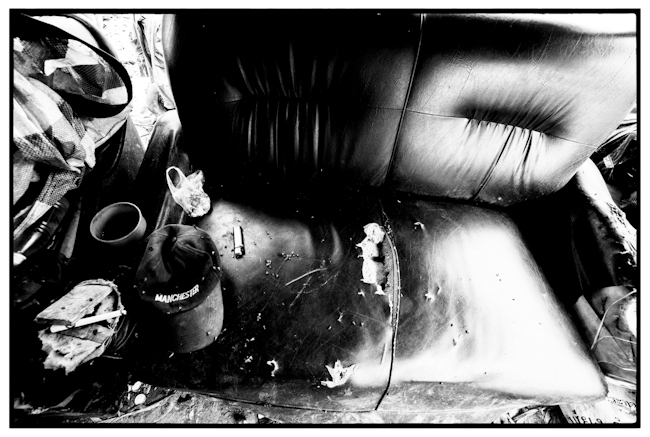

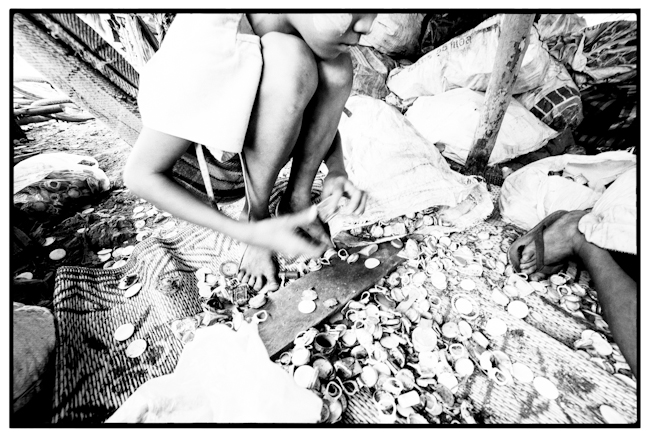

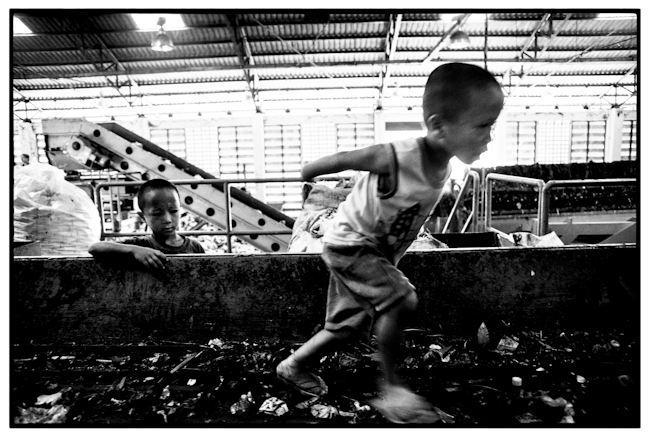

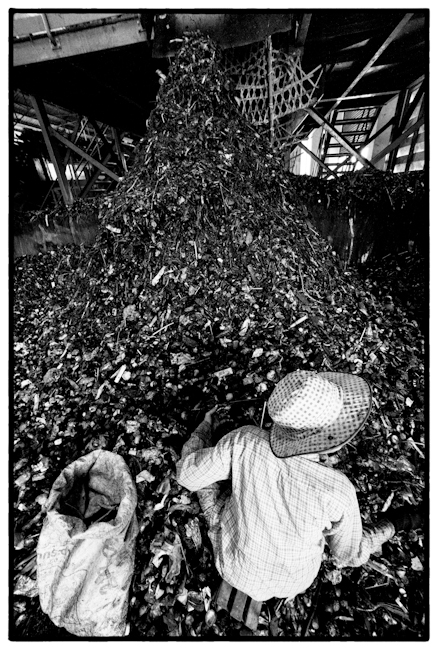

Photography. Sebastian Vilariño Text. Agustina Vigano The System’s Leftover In MaePa, only 10 minutes away from the border city of Maesot between Thailand and Burma, a mountain of garbage dominates the landscape. A green lake glows of pollution while barefoot children under 10 years old seek treasures between decomposing batteries, remains of cookies packs, polyestyrene trays and plastic bags. At the foot of the mountain, onto a carpet of the system’s waste, settles houses of burmese illegal inmigrants. 200 people -and each year more and more families- find this place as the only option for survival. They belong to different ethnic groups who ran away from their homeland escaping from hunger, unemployment and repression from a dictatorship that has been ruling the country for more than 60 years. Recycling… Twice a day the garbage truck arrives at the four factories surrounding the dump, bringing between 50 to 60 tons a day. Both women and men spend their days separating metal, glass, plastic and organic waste while their children play among rubbish searching recyclable materials to sell. Factories are open everyday because people throw trash everyday. Workers are provided with masks (which prefer not to wear despite the nauseating smell), latex gloves and a stick to stir residues which come on a belt before them to separate recyclable materials. Plastic bags are dried to be sold to other factories that melt them to produce plastic items such as chairs and tables, the organic matter is digested into small pieces to produce BioGas, glass bottles and metals are sold and what is left is burned in an incinerator. This unhealthy work pays between 100 and 120 bhats a day, barely enough to feed their family. The houses made of bamboo, metal and waste do not have electricity or drinking water. As the land belongs to the government, they don’t pay any rent but do pay the price with their health: they face severe respiratory problems, skin infections from walking barefoot, stomach problems from drinking polluted water, nutritional deficiency and dengue. …And Survival These families come from an even worst reality: in Burma there is no job, no access to land for farming and the government often obliged them to forced labour. Thai government is aware of their situation and allows them to settle in the dump because they do the job no one else is willing to do; their illegal inmigrant status and lack of contacts leaves them very few alternatives. Refugee camps would welcome them but many don’t know the right people to enter and some prefer to work to support their children rather to loose their freedom. So they stay here and don’t see any possibilities to change their lives -at least in the short term. To make matters worse, police have these families threatened and living in constant fear: twice a month they visit the houses demanding money in order to stay there. Those who can’t pay grab their bags and run to hide in the forest to avoid being caught and deported back to Burma, their homeland and their worst nightmare. Children who were born in the dump don’t feel the putrid smell of the air. In the courtyard of their homes lies the reality which the consumption system wants to hide from us: everything we buy, consume and throw away has non-biodegradable components that stay there beneath the feet of innocent kids who still don’t know what was inside these packagings –and they might never know. For them is just a game or competition of who finds more or better stuff. They walk through the corridors of the garbage mountain mindful not to sink in cesspit of decomposition, with their bags on the shoulders where they keep recyclable objects, found toys and even remains of things to eat. The leftovers of the system are not only material: are also these people dispossessed and forgotten who see the world through the waste of others.